The Real Reason Your Vote Doesn't Count

The Electoral College and Gerrymandering, not Voting Fraud, Are Stealing the Power from Our Votes

If you are an eligible American voter, there is an 82.3 percent chance that your vote does not count in the presidential election, and an 80.2 percent chance that your vote does not count in selecting your congressional representative.

Overly negative? How do I justify such a precise dismissal of our hallowed democratic system? Do you want to know how I arrive at those figures?

Electoral College Math

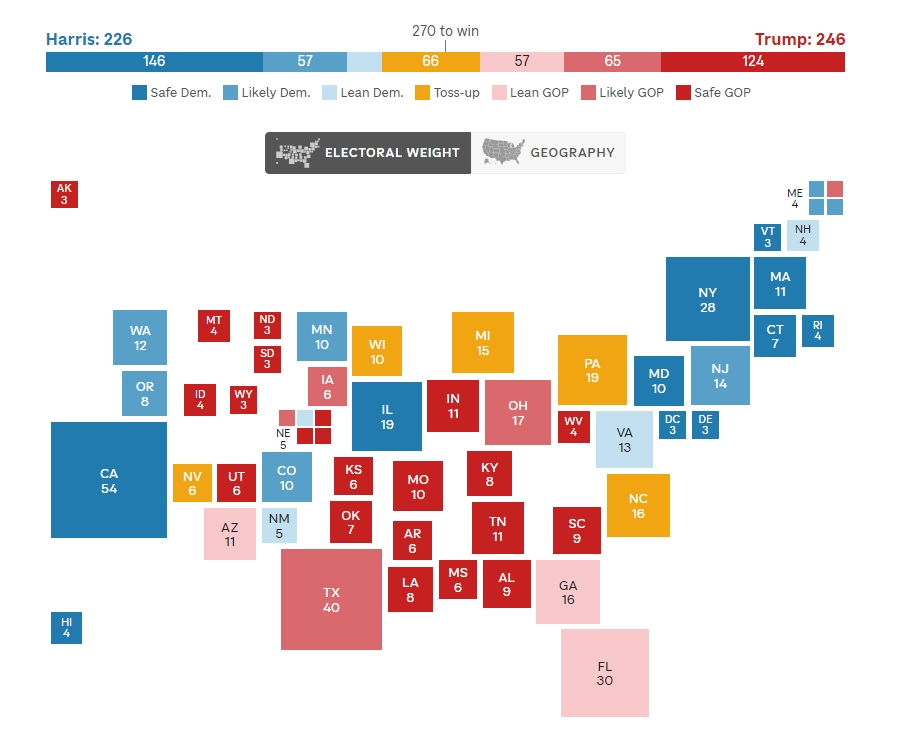

America keeps going to the electoral college but does not seem to be getting any smarter. Each of us is effectively gerrymandered into a state (not counting those disenfranchised completely in Washington, D.C., and U.S. Territories), and our states have certain voting proclivities. There is zero likelihood that California will vote for the Republican nominee. There is zero likelihood that Alabama will vote for the Democratic nominee. So if you like me live in one of these “safe” states, no amount getting out the vote or organizing is going to make any difference: your state’s electoral votes are going to the preordained choice. Said differently, your vote does not count or matter.

If only a few states were in this situation, it would perhaps not be such a serious problem. But in reality, only a very few states are conceivably up for grabs, and their population is only approximately 17.7 percent of the total United States population:

Michigan (pop. 10.1 million)

Wisconsin (pop. 5.9 million)

Pennsylvania (pop. of 13.0 million)

Georgia (pop. 10.7 million)

Arizona (pop. 7.4 million)

Nevada (pop. 3.1 million)

North Carolina (pop. 10.8 million) (maybe a swing state)

These “swing states” have a total population of 61 million out of a total U.S. population of 345 million (i.e., 17.7 percent). Thus, the 82.3 percent of the rest of us who do not live in one of these swing states will have no say in who the next president is.

Because U.S. Senate districts are also just the states, the numbers are the same for the choosing your senator. Only 17.7 percent of us have any choice when it comes to the general election for our senators.

Another way the electoral college steals votes is the overrepresentation of small-population states as compared to states with larger populations. This, of course, is a vestige of the dynamics at the original constitutional convention, where 13 sovereign nations were working to form a common national government. But what relevance do those concerns have to the subsequently created political subdivisions (Texas excepted) like North and South Dakota, California, and Wyoming? The result of the continuation of the smaller states both in the electoral college and in the bicameral legislature is that a Wyoming voter counts roughly 4x as much as a California voter. Al Letson describes it well:

So you’re voting to deliver your state’s Electoral College votes to one of the candidates, that’s important. So listen up, California has 54 electoral votes, 54. That comes out to roughly one vote every 730,000 people. Now, let’s compare that to Wyoming, a state with three Electoral College votes. That’s about one for every 190,000 people.

See Not All Votes Are Created Equal - Reveal.

Are citizens of Wyoming that much more important than citizens of California? What justifies this tremendous disparity? Does anyone want to argue that giving Wyoming citizens 4x the voting power of Californians is fair?

State Legislatures Gerrymander Away Your Vote

There are 435 congressional districts, each of which is up for reelection every two years. These are much smaller units than the 50 states and have roughly equal population in each, though, so it follows that they will be much more responsive to the people, right? Surely your vote counts in your congressional district, right?

Nope. And don’t call me Shirley.

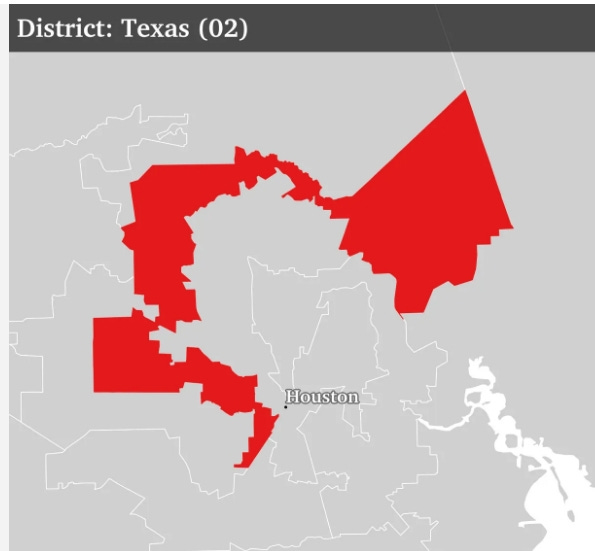

Congressional districts are drawn by the individual state legislatures. Political gerrymandering, meaning drawing a district with the objection of achieving a particular electoral outcome, is perfectly legal under the federal Constitution. See, e.g., Rucho v. Common Cause, 588 U.S. 684 (2019). Both parties, therefore, have set about drawing congressional maps to dilute the opposite parties’ voters so that they can never win an election (cracking) and, failing that, putting all of the opposite parties’ voters into very few districts so that they can win fewer seats (packing).

The result is that of the 435 congressional districts, only roughly 86 districts have a ±5 on the CPVI, meaning that they are competitive within 5 percentage points. See Cook Political Report, Cook PVI. Far fewer will actually turnover. A tumultuous election would usually see a 15-20 seat shift. The districts are roughly equal in population, and therefore only approximately 19.8 percent of Americans live in a district that even has a chance to flip. The votes of the other 80.2 percent of us do not count or matter in congressional races.

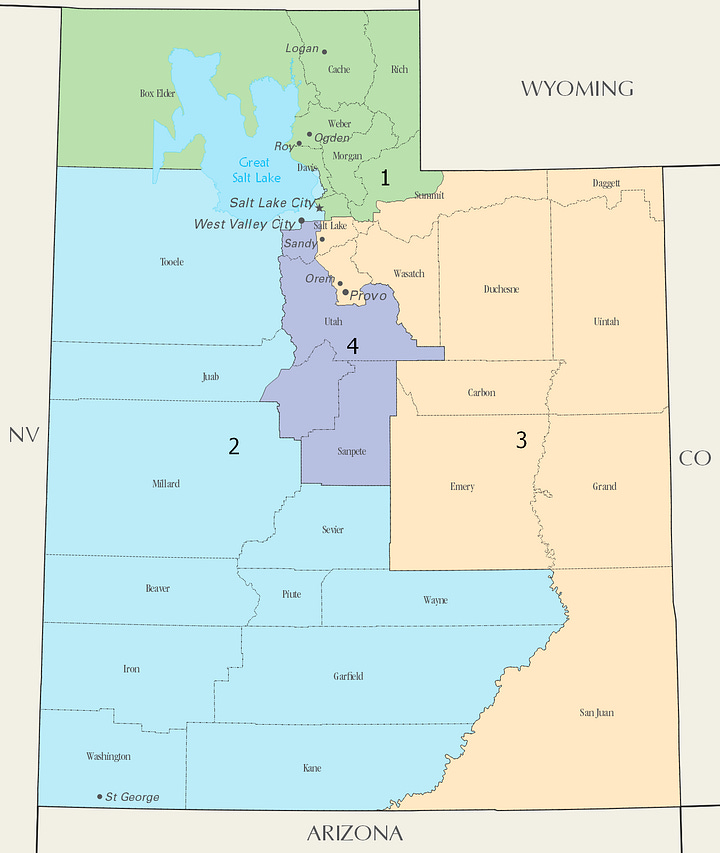

I live in a completely gerrymandered state that has a 100% locked-in all Republican delegation. In the 2010s, due to demographic changes, the second congressional district in Utah was occasionally up for grabs. If the Democrats poured in money and the Republicans were having a bad year, it might be close. This situation of near fairness - one purple district of four for a state with roughly 44% Democratic-leaning voters - was intolerable to the Utah legislature. So it was quite an achievement for the Utah legislature to take Salt Lake County and slice it up like a pizza so that those voters can never elect a Democrat to represent them:

How do you think those disenfranchised voters feel? Do they feel like they live in a democracy? Do they feel like government represents them? Do they feel like the Utah legislature cares about them or their values, their families, or their needs? The Utah legislature has taken away their vote, their vote is not needed to maintain the Republican grip on power, so why would the Republicans in office do anything to help these people? But Republicans shouldn’t rejoice either, because what incentive do their representatives have to do anything for you if they are never in danger of losing their seat?

* * *

It is very likely that your state representative and senate districts and even your city council and other representative districts are also similarly gerrymandered. Mine are. My vote will not matter. I’ll vote anyway.

Note that your vote does not matter even if you live in a district that always votes for the party you favor. If you are a staunch Republican and live in a safe Republican district, the fact that your vote does not matter also disenfranchises you. The problem is that your representative does not need your vote. So why would your representative deliver for you or be responsive to your concerns? If your vote and the vote of your neighbors has no chance of knocking them out of power, do you live in a democracy?

Is Democracy in the United States Succeeding?

How do we measure success of a democracy?

Many seem to want to use the prosperity of the economy, the economic equality or inequality of its citizens, the economic growth relative to other countries, the military might, the happiness or complacency of its citizenry, or some other metric that actually has no relationship to whether the state is a functioning democracy. I reject these as, at best, side effects of any given political system and more likely effects of resources, history, population, demographics, and other things not directly correlated with deo

How should we measure the strength of our democracy then? My suggestion is the first, true measure of a democracy is whether it is, in fact, a representative democracy. Do the voters have input into who represents them? In this case, only 17-19 percent of eligible voters have any input. Our system consists of (1) historically ossified state blocs that disenfranchise 80 percent of our population in senate and presidential races; and (2) hyper-partisan gerrymandered voting districts for other offices that have evolved simply because parties in power naturally seek to entrenches themselves. So our democracy is failing not because democracies are not a good form of government but because we are no longer effectively a democracy (if we ever were).1

I live in the State of Utah. My vote will not matter. I’m seeing few political ads. Neither Trump nor Harris is holding political rallies in Salt Lake City. No one is canvassing and trying to ensure I mail in my ballot or asking if I need a ride to the polls on election day. That is because everyone recognizes that my vote and the votes of everyone else in this state don’t matter.

Despite an alarmingly high number of our fellow citizens, especially those on the far right, viewing authoritarianism favorably, the strong preference for living in a responsive, representative democracy is pretty universal. If democracy were truly working and each of us knew our votes mattered, surely even more would be in favor. So the first effect of disenfranchisement is disillusionment of the voters. They don’t care. Turnout goes down. Faith in government and institutions is at an all-time low. And democracy weakens.

But the disconnect between voter power and representation has another effect. It is not just the voters who feel like they are not represented: it is also the elected representatives who feel like they don’t have to work to gain the approval of their voters. It is the most fundamental responsibility of the government at all levels to plead for the affections of and deliver for the benefit of all of the people they represent. This system of gerrymandered representation takes that away. Now, if they represent a “safe” district, all they have to please are the party bosses and hard liners who keep them on the ballot with a “R” or “D” by their name. This will have a positive feedback cycle, too, as representatives do not listen to those they represent, and, so, again, the voters will feel that their representatives do not care, and the disconnect deepens.

Democracy Is Made to Be Reformed

So, our democracy is not democracy-ing. What is there to do?

One of the great innovations of our Constitution is that it can be amended. It is not handed down from God in its current form, never to be altered. It has been amended 27 times and, in fact, was amended as recently as 1992. The difficulty, of course, lies in the political economy: can we get a sufficient coalition together to implement amendments to the Constitution to modernize it to make more of our fellow citizens’ votes count? Currently, a minority population that overrepresents white, rural, and southern voters greatly benefits from the electoral college. These historic and evolved systems empower the very people who have a blocking position preventing any change, at least at the constitutional level.

Are there changes that we can make at other levels that would help? Yes. A number of states, including Utah, have passed anti-gerrymandering laws though the referendum process. Citizens in other states have successfully gerrymandered districts based on equal-representation clauses in their state constitutions.2 Entrenched political interests, however, have shown they will go to great lengths, including outright ignoring citizen-passed laws and judicial rulings to maintain their gerrymandered power structure. In Utah, the state legislature simply ignored the citizen-passed redistricting initiative and passed its own maps, leading to a fight all the way to the Utah Supreme Court. In Alabama, a federal court struck down on racial gerrymandering grounds the state’s new district map as it impermissibly packed black voters into a compact district and diluted the remainder of black votes across multiple other districts. When the map was struck down, however, the legislature simply ignored the court’s mandate to re-draw it, causing the courts to have to step in and do it themselves.

It is clear, however, that public sentiment is overall against gerrymandering. Since these battles are on the state level, there may be a more effective effort to be made.

The difficulty lies most prominently and perhaps permanently with the federal Constitution and the electoral college. The amendment process requires such a high bar that, so long as the significant minority benefits, no amendment taking away that benefit is very likely.

Change is always impossible until it isn’t. A friend of mine recently told me that it would take repeated disastrous minority rule to offend people into forcing a change. Maybe she is right. My hope is that we can avoid a constitutional crisis and make incremental changes and at least begin the discussion on larger ones to make our democracy work. I think we all can agree that we would rather live in a society in which all, not just 17-20 percent of our votes, count and matter.

* * *

If you enjoyed reading this, please subscribe.

If you would like to start a conversation, please share these ideas with your friends.

According to the Federalist Papers, the idea behind the electoral college and bicameral legislature at the founding was to protect against the rule of the unwashed masses, i.e., because the idea of a pure democracy was suspect at the time. See Madison, Federalist 51. We first implemented these principles of rule by elites for historical reasons, but we retain them because a sufficient number of people who benefit from them decline to consent to their abolition through the amendment process, not because they are necessary or beneficial.

Wang, et al., LABORATORIES OF DEMOCRACY REFORM: STATE CONSTITUTIONS AND PARTISAN GERRYMANDERING, Penn. J. Constitutional L., Vol. 22, p. 204.